Week 02: Running Times (Lab)

2026-01-15

Intro

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lab, you should be able to:

- Apply asymptotic notation and the Master Theorem to analyze divide-and-conquer algorithms.

- Implement divide-and-conquer algorithms as recursive functions, handling base cases and subproblem decomposition.

- Explain why two algorithms with the same asymptotic complexity can have different real-world performance.

- Analyze running-time measurements to verify theoretical predictions.

Overview of Lab Activities

Submit your work for the following activities to xSITe and/or Gradescope (as specified on each slide):

- Multiple-Choice Questions:

Answer four questions on asymptotic notation and the Master Theorem. - Triple-Loop Matrix Multiplication:

Implement the straightforward \(i\)-\(j\)-\(k\) loop algorithm. - 8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication:

Implement the divide-and-conquer algorithm. - Benchmarking and Analysis:

Measure running times and compare with theoretical predictions.

Recap: \(O\), \(\Omega\), and \(\Theta\) Notation

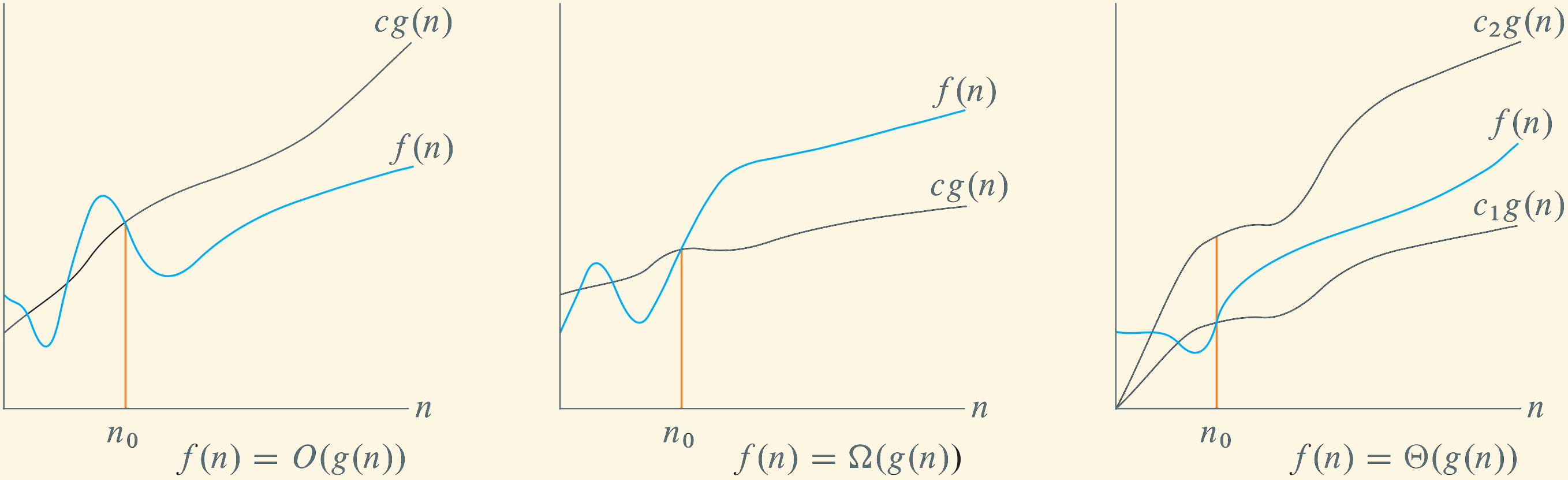

The lecture introduced asymptotic notation to describe the growth of a function \(f(n)\):

- \(\boldsymbol{O(g(n))}\): upper bound (grows no faster than)

- \(\boldsymbol{\Omega(g(n))}\): lower bound (grows at least as fast as)

- \(\boldsymbol{\Theta(g(n))}\): tight bound (same order of growth)

The picture below summarizes the idea: for sufficiently large \(n\), \(f(n)\) is above, below, or between multiples of \(g(n)\).

Multiple-Choice Questions

Multiple-Choice Questions

On the xSITe course page, navigate to Assessments → Quizzes → Week 02 Lab Exercise 1: Multiple Choice Questions — Running Times of Algorithms.

Select the best answer for each of the following four questions. You may refer to your notes or the lecture slides.

Exercise 1: Question 1

Suppose an algorithm allocates an array \(a\) of length \(n\), where each element is a 32-bit integer. The algorithm computes the following sum using a nested loop:

\[ S = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}\sum_{j=0}^{n-1} a[i] \cdot a[j] \]

Which statement best aligns with the standard definition of basic steps in asymptotic analysis?

- Each multiplication \(a[i] \cdot a[j]\) is a basic step only when \(i = j\).

- Each multiplication \(a[i] \cdot a[j]\) is not a basic step because there are \(n^2\) total multiplications.

- Each multiplication \(a[i] \cdot a[j]\) is a basic step because both operands are fixed-width 32-bit integers.

- Whether \(a[i] \cdot a[j]\) is a basic step depends on whether \(n\) is a power of 2.

Answer to Question 1

Correct Answer: c

Reasoning:

In the word-RAM model, arithmetic operations (like addition or multiplication) on fixed-width machine words are treated as constant-time \(\boldsymbol{O(1)}\) basic steps.

- Since the integers are 32-bit, the time to multiply them does not grow as \(n\) increases.

- Choice (b) is a common misconception: while the total number of steps depends on \(n\), the definition of a single basic step depends only on the hardware’s ability to process the operands in constant time.

Exercise 1: Question 2

Consider the following pseudocode, where a is an array of length \(n\):

for i ← 0 .. n - 1 (both end points inclusive)

if i > 0 then

for j ← 0 .. i - 1

a[i] ← i - j

Exactly how many times is the assignment to a[i] executed, as a function of \(n\)?

- \(n(n+1)/2\)

- \(n^2\)

- \(n(n-1)/2\)

- \(n\)

Answer to Question 2

Correct Answer: c

Reasoning:

For each iteration of the outer loop (fixed \(i\)), the inner loop runs exactly \(i\) times (for indices \(0, \ldots, i-1\)). To find the total executions, we sum \(i\) for all iterations of the outer loop:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Total executions} &= \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} i = 0 + 1 + 2 + \ldots + (n-1) \\ &= \frac{(n-1)n}{2}\ . \end{align*}\]

Note: When \(i = 0\), the range \(0, \ldots, -1\) is empty, so the inner loop does not run. This matches the first term of our sum being 0.

Exercise 1: Question 3

For sufficiently large \(n\), which ordering from slowest-growing to fastest-growing is correct?

\[\begin{align*} \text{a.}\quad & O(\log^2 n) &&\subset\quad O(\sqrt{n}) &&\subset\quad O(n) &&\subset\quad O(n\log n) \\ \text{b.}\quad & O(\log^2 n) &&\subset\quad O(n) &&\subset\quad O(\sqrt{n}) &&\subset\quad O(n\log n) \\ \text{c.}\quad & O(\sqrt{n}) &&\subset\quad O(\log^2 n) &&\subset\quad O(n) &&\subset\quad O(n\log n) \\ \text{d.}\quad & O(\log^2 n) &&\subset\quad O(\sqrt{n}) &&\subset\quad O(n\log n) &&\subset\quad O(n) \end{align*}\]

Answer to Question 3

Correct Answer: a

Reasoning:

\(\boldsymbol{\log^2 n}\) versus \(\boldsymbol{\sqrt{n}}\):

For any powers \(k > 0\) and \(\epsilon > 0\), \((\log n)^k\) grows strictly slower than \(n^\epsilon\). Here, \(k=2\) and \(\epsilon=0.5\); thus, \(O(\log^2 n) \subset O(\sqrt{n})\).

\(\boldsymbol{\sqrt{n}}\) versus \(\boldsymbol{n}\):

We compare the exponents: \(\sqrt{n} = n^{1/2}\) and \(n = n^1\). Because \(\frac{1}{2} < 1\), the square root grows slower than the linear term.

\(\boldsymbol{n}\) versus \(\boldsymbol{n \log n}\):

For sufficiently large \(n\), we have \(\log n > 1\). Hence, multiplying \(n\) by \(\log n\) makes it grow faster than \(n\) alone.

Thus, the chain is \(O(\log^2 n) \subset O(\sqrt{n}) \subset O(n) \subset O(n\log n)\).

Exercise 1: Question 4

Use the Master Theorem to solve the recurrence \(T(n) = 3T(n/2) + n\). What is the asymptotic solution?

Master Theorem

Let \(a \ge 1\) and \(b > 1\) be constants, and let \(f(n)\) be a function with \(f(n) \ge 0\) for all sufficiently large \(n\). Consider recurrences of the form \(T(n) = a\,T\left(\frac{n}{b}\right) + f(n)\) for values of \(n\) for which the recurrence is defined (e.g., \(n=b^k\)). Let \(p = \log_b a\).

- If \(f(n) \in O\bigl(n^{p-\varepsilon}\bigr)\) for some \(\varepsilon > 0\), then \(T(n) \in \Theta\bigl(n^p\bigr)\).

- If there exists \(k \ge 0\) such that \(f(n) \in \Theta\bigl(n^p \log^k n \bigr)\), then \(T(n) \in \Theta\bigl(n^p \log^{k+1} n\bigr)\).

- If \(f(n) \in \Omega\bigl(n^{p+\varepsilon}\bigr)\) for some \(\varepsilon > 0\) and there exist constants \(c < 1\) and \(n_0\) such that for all \(n \ge n_0\) we have \(a\,f\left(\frac{n}{b}\right) \le c\,f(n)\), then \(T(n) \in \Theta\bigl(f(n)\bigr)\).

a. \(\Theta(n^2)\quad\) b. \(\Theta(n)\quad\) c. \(\Theta(n \log n)\quad\) d. \(\Theta(n^{\log_2 3})\quad\)

Answer to Question 4

Correct Answer: d.

For the recurrence \(T(n) = 3T(n/2) + n\), we identify: \[a = 3, \quad b = 2, \quad f(n) = n\]

Step 1—Calculate the critical exponent \(\boldsymbol{p}\): \[p = \log_b a = \log_2 3 \approx 1.585\]

Step 2—Compare \(\boldsymbol{n^p}\) with \(\boldsymbol{f(n)}\):

We compare \(n^{\log_2 3}\) with \(f(n) = n^1\). Because \(1 < \log_2 3\), \(f(n)\) grows polynomially slower than \(n^p\); consequently case 1 of the Master Theorem applies. Specifically, \(n^1 \in O\bigl(n^{\log_2 3 - \epsilon}\bigr)\) for some \(\epsilon > 0\) (e.g., \(\epsilon = 0.5\)).

Conclusion: \(T(n) = \Theta(n^p) = \Theta(n^{\log_2 3})\)

Matrix Multiplication

Matrix Multiplication: Problem Statement

We study the running time of algorithms that multiply two square matrices.

Given two \(n\times n\) matrices \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\), the product matrix \(\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{A}\cdot \mathbf{B}\) has elements defined by \[ C_{ij} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} A_{ik} B_{kj}. \]

Hence, each element \(C_{ij}\) is the dot product of \(\mathbf{A}\)’s \(i\)-th row with \(\mathbf{B}\)’s \(j\)-th column. Note that we adopt 0-based indexing.

Input Format for Matrices

You can test your code by providing input matrices from a text file with the following format:

- The first line contains a single integer \(n\), representing the number of rows/columns.

- The file then lists \(\mathbf{A}\), \(\mathbf{B}\), and \(\mathbf{C}_{\text{expected}} = \mathbf{A}\cdot\mathbf{B}\) (each \(n\) rows); numbers in a row are comma-separated.

- Blank lines are ignored, and

#starts a comment.

C++ Implementation Overview

Download the starter code from GitHub Pages. The ZIP archive contains a C++ project for the exercises on the following slides:

main_*.cpp- Entry points for programs that perform specific tasks, such as correctness checks and benchmarking

matrix_utilities.cppandmatrix_utilities.h- Matrix types and helper functions (including input parsing)

matmul_*.cppandmatmul_*.h- Stubs for matrix-multiplication algorithms

vega_lite_plot.cppandvega_lite_plot.h- Utilities for plotting

makefile-

File to compile the project using

make

Understanding the Matrix Type

The starter code defines the matrix type in matrix_utilities.h:

MatrixInt64is a type alias for a 2D vector of 64-bit signed integers.Access element \((i, j)\) as

matrix[i][j].Create an \(n \times n\) zero matrix:

Why int64_t? When multiplying large matrices, intermediate sums can overflow 32-bit integers (even when the input entries fit in 32-bit). Using 64-bit integers provides a safety margin.

Triple Loop

Exercise 2a: Triple-Loop Matrix Multiplication

Recall the definition of matrix multiplication: \(C_{ij} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} A_{ik} B_{kj}.\) Your task is to implement this summation as a triple loop over \(i\), \(j\), and \(k\) (in this order). In the provided ZIP archive, complete the function stub matmulIJK() in matmul_ijk.cpp.

To compile and test locally, run the following commands:

Upload your solution to Gradescope. Detailed instructions are provided on xSITe (Dropbox \(\rightarrow\) Week 02 Lab Exercise 2a: Gradescope—Triple-Loop Matrix Multiplication).

Solution: Triple-Loop Matrix Multiplication

The following triple loop is a direct translation of \(C_{ij} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} A_{ik} B_{kj}\), using indices in the order \(i\)-\(j\)-\(k\). You might need to scroll down to view the entire code:

#include "matmul_ijk.h"

#include <stdexcept>

MatrixInt64 matmulIJK(const MatrixInt64 &matrix_a,

const MatrixInt64 &matrix_b) {

const std::size_t n = matrix_a.size();

if (n == 0) {

throw std::invalid_argument("matmulIJK expects non-empty matrices");

}

if (matrix_b.size() != n) {

throw std::invalid_argument("matmulIJK expects matrices of the same size");

}

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

if (matrix_a[i].size() != n || matrix_b[i].size() != n) {

throw std::invalid_argument("matmulIJK expects square matrices");

}

}

MatrixInt64 matrix_c(n, std::vector<std::int64_t>(n, 0));

// Straightforward iterative multiplication (i-j-k).

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (std::size_t j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

std::int64_t sum = 0;

for (std::size_t k = 0; k < n; ++k) {

sum += matrix_a[i][k] * matrix_b[k][j];

}

matrix_c[i][j] = sum;

}

}

return matrix_c;

}Divide and Conquer

8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication: Key Idea

Block-recursive matrix multiplication is a divide-and-conquer algorithm that multiplies matrices by splitting them into equally-sized quadrants:

\[\begin{equation*} \mathbf{A}= \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{A}_{11} & \mathbf{A}_{12}\\ \mathbf{A}_{21} & \mathbf{A}_{22} \end{pmatrix},\quad \mathbf{B}= \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{B}_{11} & \mathbf{B}_{12}\\ \mathbf{B}_{21} & \mathbf{B}_{22} \end{pmatrix},\quad \mathbf{C}= \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{C}_{11} & \mathbf{C}_{12}\\ \mathbf{C}_{21} & \mathbf{C}_{22} \end{pmatrix}. \end{equation*}\]

Then compute the four blocks of \(\mathbf{C}\) using 8 smaller multiplications (plus 4 additions):

\[\begin{equation*} \begin{aligned} \mathbf{C}_{11} &= \mathbf{A}_{11}\mathbf{B}_{11} + \mathbf{A}_{12}\mathbf{B}_{21}\\ \mathbf{C}_{12} &= \mathbf{A}_{11}\mathbf{B}_{12} + \mathbf{A}_{12}\mathbf{B}_{22}\\ \mathbf{C}_{21} &= \mathbf{A}_{21}\mathbf{B}_{11} + \mathbf{A}_{22}\mathbf{B}_{21}\\ \mathbf{C}_{22} &= \mathbf{A}_{21}\mathbf{B}_{12} + \mathbf{A}_{22}\mathbf{B}_{22}\\ \end{aligned} \end{equation*}\]

Divide and Conquer: Why Power-of-2 Sizes?

The recursive algorithm splits matrices into equal quadrants. This procedure requires the matrix dimension to be divisible by 2 at each level of recursion.

Problem: If \(n\) is not a power of 2 (e.g., \(n=3\)), we cannot split evenly all the way down to \(1 \times 1\) submatrices.

As the following slide explains, we solve this issue by padding the input matrices with zeros if necessary.

Divide and Conquer: Padding

- Find the smallest power of 2 that is \(\ge n\). The C++ code calls this number

padded_dim. For example, if \(n=3\), thenpadded_dim = 4. - Embed \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) in

padded_dim-by-padded_dimmatrices, filling extra elements with zeros. - Multiply the padded matrices using the recursive algorithm.

- Extract the top-left \(n \times n\) block of the result.

Why Padding Preserves Correctness

Consider the product \(C_{ij} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} A_{ik} B_{kj}\).

When we pad \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) with zeros to size padded_dim \(> n\):

- For \(\boldsymbol{i, j < n}\):

The extra terms in the sum (where \(k \ge n\)) are \(A_{ik} \cdot B_{kj} = 0 \cdot B_{kj} = 0\). The result is unchanged. - For \(\boldsymbol{i \ge n}\) or \(\boldsymbol{j \ge n}\):

These elements of \(\mathbf{C}\) are zeros. We discard them.

Conclusion: The top-left \(n \times n\) block of the padded product equals the true product \(\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}\) of the unpadded matrices.

What You Need to Implement

If you haven’t already, download the starter files.

The starter code provides matmulDivideConquer8(), a wrapper function with padding logic already implemented.

Your task: Implement the recursive helper function blockMatmulAdd() that:

- Handles the base case (\(1 \times 1\) submatrix).

- Computes the 8 recursive calls for the four quadrants of \(\mathbf{C}\):

- \(\mathbf{C}_{11} \mathrel{+}= \mathbf{A}_{11}\mathbf{B}_{11}\), then \(\mathbf{C}_{11} \mathrel{+}= \mathbf{A}_{12}\mathbf{B}_{21}\)

- Similarly for \(\mathbf{C}_{12}\), \(\mathbf{C}_{21}\), \(\mathbf{C}_{22}\)

Exercise 2b: 8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication

To implement matrix multiplication recursively, complete the recursive helper function blockMatmulAdd() in matmul_divide_conquer.cpp, provided in the ZIP archive. The wrapper matmulDivideConquer8(), including padding and input checks, is already implemented.

Implementation trick: Do not copy \(A_{11},A_{12},\dots\) into new matrices. Instead, treat each submatrix as a view into the entire \(n\times n\) matrix: represent it by (row_offset, col_offset, size) and access elements via index offsets.

To compile and test locally, run the following commands:

Upload your solution to Gradescope. Detailed instructions are provided on xSITe (Dropbox \(\rightarrow\) Week 02 Lab Exercise 2b: Gradescope—8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication).

Solution: 8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication (Part 1)

static void blockMatmulAdd(const MatrixInt64 &matrix_a,

std::size_t a_row_offset, std::size_t a_col_offset,

const MatrixInt64 &matrix_b,

std::size_t b_row_offset, std::size_t b_col_offset,

MatrixInt64 &matrix_c, std::size_t c_row_offset,

std::size_t c_col_offset, std::size_t n) {

// Base case: 1x1 submatrix

if (n == 1) {

matrix_c[c_row_offset][c_col_offset] +=

matrix_a[a_row_offset][a_col_offset] *

matrix_b[b_row_offset][b_col_offset];

return;

}

const std::size_t h = n / 2;

// c11 += a11*b11; c11 += a12*b21

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset, a_col_offset, matrix_b, b_row_offset,

b_col_offset, matrix_c, c_row_offset, c_col_offset, h);

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset, a_col_offset + h, matrix_b,

b_row_offset + h, b_col_offset, matrix_c, c_row_offset,

c_col_offset, h);

// c12 += a11*b12; c12 += a12*b22

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset, a_col_offset, matrix_b, b_row_offset,

b_col_offset + h, matrix_c, c_row_offset, c_col_offset + h, h);

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset, a_col_offset + h, matrix_b,

b_row_offset + h, b_col_offset + h, matrix_c, c_row_offset,

c_col_offset + h, h);

// c21 += a21*b11; c21 += a22*b21

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset + h, a_col_offset, matrix_b,

b_row_offset, b_col_offset, matrix_c, c_row_offset + h,

c_col_offset, h);

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset + h, a_col_offset + h, matrix_b,

b_row_offset + h, b_col_offset, matrix_c, c_row_offset + h,

c_col_offset, h);

// c22 += a21*b12; c22 += a22*b22

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset + h, a_col_offset, matrix_b,

b_row_offset, b_col_offset + h, matrix_c, c_row_offset + h,

c_col_offset + h, h);

blockMatmulAdd(matrix_a, a_row_offset + h, a_col_offset + h, matrix_b,

b_row_offset + h, b_col_offset + h, matrix_c, c_row_offset + h,

c_col_offset + h, h);

}

Solution: 8-Fold Block-Recursive Matrix Multiplication (Part 2)

MatrixInt64 matmulDivideConquer8(const MatrixInt64 &matrix_a,

const MatrixInt64 &matrix_b) {

const std::size_t n = matrix_a.size();

if (n == 0) {

throw std::invalid_argument(

"matmulDivideConquer8 expects non-empty matrices");

}

if (matrix_b.size() != n) {

throw std::invalid_argument(

"matmulDivideConquer8 expects matrices of the same size");

}

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

if (matrix_a[i].size() != n || matrix_b[i].size() != n) {

throw std::invalid_argument(

"matmulDivideConquer8 expects square matrices");

}

}

const std::size_t padded_dim = std::bit_ceil(n); // Smallest power of 2 >= n

const MatrixInt64 *a_ptr = &matrix_a;

const MatrixInt64 *b_ptr = &matrix_b;

MatrixInt64 a_pad, b_pad;

MatrixInt64 matrix_c(n, std::vector<std::int64_t>(n, 0));

MatrixInt64 *c_ptr = &matrix_c;

MatrixInt64 c_pad;

if (padded_dim != n) { // Pad to the next power of two.

a_pad.assign(padded_dim, std::vector<std::int64_t>(padded_dim, 0));

b_pad.assign(padded_dim, std::vector<std::int64_t>(padded_dim, 0));

c_pad.assign(padded_dim, std::vector<std::int64_t>(padded_dim, 0));

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (std::size_t j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

a_pad[i][j] = matrix_a[i][j];

b_pad[i][j] = matrix_b[i][j];

}

}

a_ptr = &a_pad;

b_ptr = &b_pad;

c_ptr = &c_pad;

}

blockMatmulAdd(*a_ptr, 0, 0, *b_ptr, 0, 0, *c_ptr, 0, 0, padded_dim);

if (padded_dim != n) { // Extract result from padded matrix.

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (std::size_t j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

matrix_c[i][j] = c_pad[i][j];

}

}

}

return matrix_c;

}

Benchmarking

From Theory to Measurement

Asymptotic notation tells us how an algorithm’s running time grows as the input size \(n\) increases. However, wall-clock time also matters: two \(\Theta(n^3)\) algorithms can differ by a large constant factor, which can significantly affect real-world performance.

In the following exercise, you will measure execution time on your computer. You do not need to write timing code yourself: a provided program runs the algorithms, measures the time, and produces a table and a plot.

Your task is to interpret the results:

- Look for the overall trend as \(n\) increases.

- Notice that constant factors and overhead can matter in practice.

Small fluctuations from run to run are normal; focus on the pattern.

Exercise 2c: Benchmarking and Analysis

Compile and run the provided benchmarking program to measure the running times of both matrix multiplication algorithms for various matrix sizes \(n\):

The optional argument max_n specifies the largest matrix dimension to benchmark (must be a power of 2, at least 8). The default is 64. For example, ./benchmark 256 tests sizes 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256. The program will output a table of running times and generate a plot.

Your task: Submit a short report (PDF or DOCX) that includes:

- The generated plot showing running time versus \(n\) for both algorithms.

- The theoretically expected running times for each algorithm, with justification.

- A discussion of whether the measurements support the theoretical predictions.

- Upload your report to xSITe (Dropbox \(\rightarrow\) Week 02 Lab Exercise 2c: Benchmarking and Analysis).

Solution: Running-Time Plot

Solution: Theoretical Running Times

Triple Loop (\(\boldsymbol{i}\)-\(\boldsymbol{j}\)-\(\boldsymbol{k}\)): \(\Theta(n^3)\). Each of the \(n^2\) elements of \(\mathbf{C}\) requires summing \(n\) products.

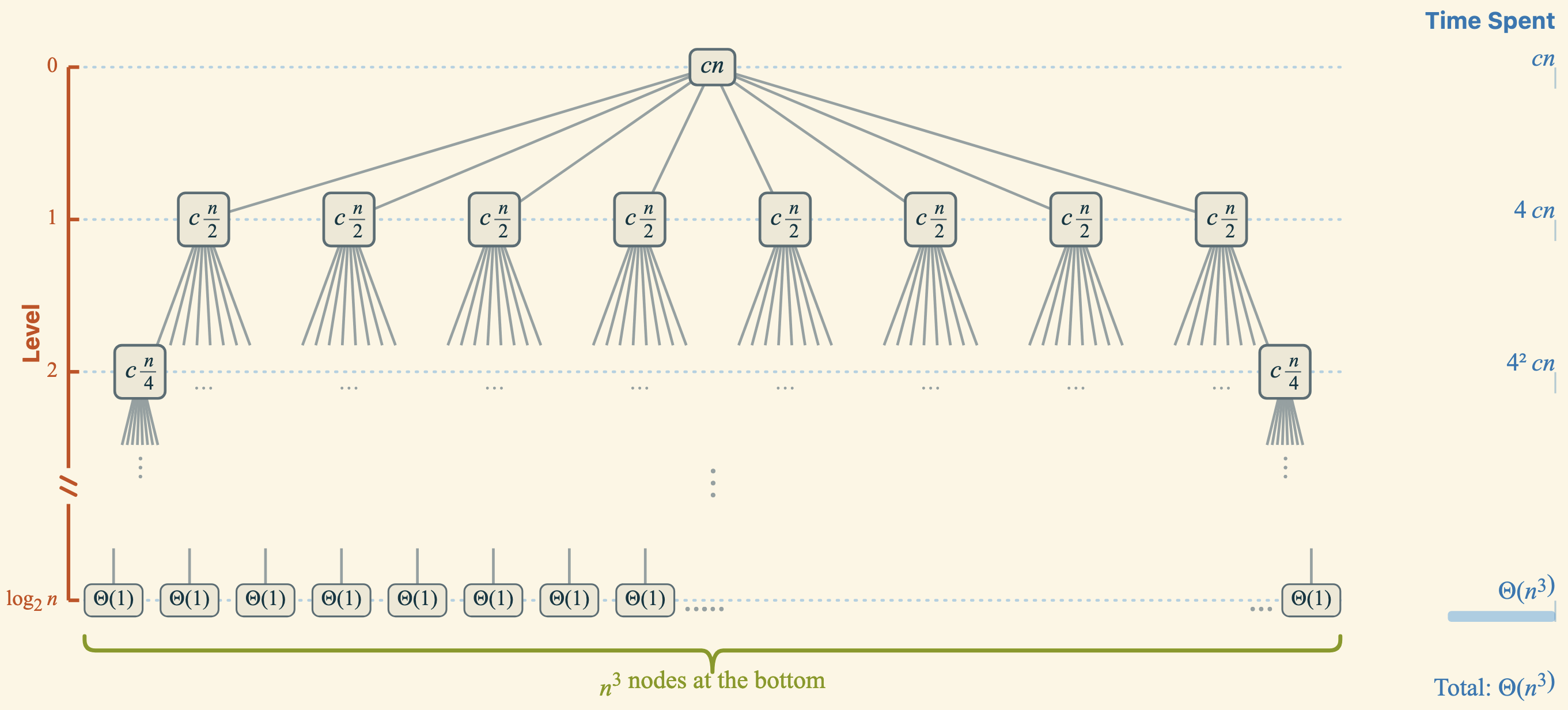

8-Fold Block Recursion: \(\Theta(n^3)\). For the recurrence \(T(n) = 8T(n/2) + \Theta(n^2)\), we have \(p = \log_2 8 = 3\). Because \(f(n) = n^2 \in O(n^{3-\epsilon})\), case 1 of the Master Theorem applies: \(T(n) = \Theta(n^3)\). The recursion tree below, created with the recursion-tree app, confirms this result.

![]()

Solution: Discussion—Asymptotic Running Time

The table below summarizes measurements from my computer. As predicted, both algorithms exhibit \(\Theta(n^3)\) growth: doubling \(n\) roughly increases time by a factor of \(2^3 = 8\) (see “Growth” columns). Focus on overall trends; small run-to-run fluctuations due to system load are normal.

| \(\boldsymbol{n}\) |

Loop (µs) |

Growth |

Recursion (µs) |

Growth |

Time Ratio (Loop/Rec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 12 | — | 20 | — | 0.60 |

| 16 | 58 | 4.8 | 123 | 6.2 | 0.47 |

| 32 | 387 | 6.7 | 926 | 7.5 | 0.42 |

| 64 | 2,066 | 5.3 | 4,277 | 4.6 | 0.48 |

| 128 | 17,037 | 8.2 | 34,810 | 8.1 | 0.49 |

| 256 | 145,357 | 8.5 | 309,081 | 8.9 | 0.47 |

| 512 | 1,135,277 | 7.8 | 2,269,617 | 7.3 | 0.50 |

Solution: Discussion—Algorithm Efficiency

Both algorithms are \(\Theta(n^3)\), yet the triple loop consistently requires only approximately half the time. Why?

Function call overhead: The triple loop performs \(\Theta(n^3)\) arithmetic operations inside a single function, whereas the recursive method makes \(\Theta(n^3)\) function calls. Each call has overhead that accumulates.

Compiler optimization: Loops are easier for compilers to optimize (e.g., loop unrolling, vectorization). Deeply recursive code is harder to analyze.

Takeaway: Asymptotic complexity captures growth rate, but constant factors—driven by implementation details—determine real-world performance.

Conclusion

Summary of Key Learning Outcomes

- Used \(O\)/\(\Omega\)/\(\Theta\) notation and the Master Theorem to classify the growth rates of divide-and-conquer recurrences. ↪

- Built a working block-recursive matrix multiplication by expressing subproblems via offsets, decomposing into quadrants, and handling the base case correctly. ↪

- Interpreted empirical performance differences between algorithms with the same \(\Theta(n^3)\) scaling, attributing gaps to constant factors (e.g., call overhead and compiler behavior). ↪

- Connected theory to data by benchmarking, checking scaling trends (e.g., when doubling \(n\)), and assessing whether the measurements align with the predicted asymptotics. ↪

Outlook

Challenges to explore on your own:

- Change the loop from \(i\)-\(j\)-\(k\) to \(i\)-\(k\)-\(j\). Faster or slower? Why?

- Replace 8-fold recursion with Strassen’s 7-fold recursion for \(\Theta(n^{2.81})\). See Section 4.2 of Cormen et al. (2022).

Next week’s topics:

This lab explored divide-and-conquer strategies and asymptotic analysis through matrix multiplication. Next week continues these themes with two classic sorting algorithms.

- Quicksort: A divide-and-conquer sorting algorithm—more practice analysing recurrences.

- Heapsort: Introduces heaps, a data structure that efficiently maintains a collection when elements are inserted or removed.

Bibliography

Week 02: Running Times (Lab)